Lessons

Mark Cuban

1:04:33 2Seth Godin

1:02:08 3Marie Forleo

1:11:22 4Tim Ferriss

1:32:51 5Arianna Huffington

42:22 6LeVar Burton

1:16:52 7Stefan Sagmeister

57:13 8Brené Brown

1:19:51Richard Branson

40:28 10Gary Vaynerchuk

45:13 11Kelly Starrett

1:38:55 12Jared Leto

31:47 13Gabrielle Bernstein

55:36 14Sir Mix-A-Lot

1:31:53 15Ramit Sethi

1:19:20 16Lewis Howes

1:10:56 17Kevin Kelly

1:13:33 18Sophia Amoruso

48:49 19Kevin Rose

1:18:03 20Brandon Stanton

1:30:33 21Daymond John

1:03:52 22Austin Kleon

1:14:50 23Neil Strauss

1:20:43 24Tina Roth Eisenberg

1:06:26 25James Altucher

1:13:47 26Brian Solis

43:42 27Gretchen Rubin

1:00:11 28Elle Luna

1:11:06 29Caterina Fake

1:08:11 30Adrian Grenier

1:18:09Lesson Info

Kevin Kelly

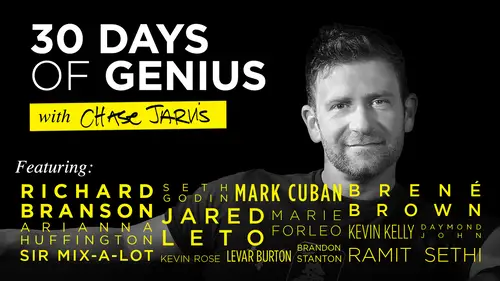

Hey, everybody, how's it going? I'm Chase Jarvis. Welcome to Creative Live and 30 Days of Genius. If you're just checking out this series for the first time, I'm sitting down with the world's top creatives, top entrepreneurs in thinking, and we are talking about actionable insights that you can take home and help improve your career, your hobby, and your life. I'm gonna extract all the information I can, and we're gonna put it on a platter for you today. If you're new to this series, go to CreativeLive.com/30, the number 3-0, daysofgenius for more information. If you click that little blue button, you'll get one of these interviews in your inbox every day for 30 days. It's a great dose of inspiration, and speaking of inspiration, my guest today, you will know him, for sure, from his accolades. He's a thought leader. He's a futurist. He's the co-founder of Wired Magazine. He is so many other things. Among them, someone who's been very influential to me. He wrote a seminal blog post call...

ed 1000 True Fans. Changed my career and the career of so many people that I know you will look up to on the internet, people that I think are the best, were all influenced by this seminal post. My guest today, none other than Mr. Kevin Kelly. Hey. Thank you so much, Kevin. (upbeat rock music) (audience applauds) They love you! Kevin, welcome to the show. Hey, it's really great. Thank you so much. I know you're a busy guy. You got a new book coming out in June, which we'll get to. We're here in Austin at South by Southwest. What's occupying your brain right now? I mean, like, today, but also, what's your focus? For the past two months, I've done a deep dive into VR, immersing myself into the immersive media, and I've tried every single VR that you could do, including Magic Leap, including Void, including Meta, including all these ones that are not so public right now. Wow. But I have been trying them all to figure out whether this time it was real, because I've been wrong about VR before. In what way were you wrong? In 1989, Jaron Lanier took me to his little office in Redwood City and I tried VR, and it was like, oh my gosh, this is real. This is the future. This is gonna happen. In 1989. And here we are. Here we are. So, I thought it was imminent. I thought it was so good that I thought it was real. The problem was that it was just too expensive, way too expensive. The real change is actually phones. Yeah, that's crazy. The screens of phones, the little accelerometers and the tracking devices in phones and the processing power in phones became so cheap. They took that same technology and put them into VR, and now you could do VR for $1,000 or less, and that's been the big change. Huge. And last year it was basically quiet on VR, and this year, that's all anyone's talking about. Everyone's walking around with these things. Exactly. Scobel can't stop talking about it. Right. So, it really is something, and I think what it's moving us from is a internet of information. Sites like yours, deliver the information, and we have Wikipedia, which is the information, and anybody in the world has access to all the information in the world, which is amazing. That's incredible. There's never a dinner table discussion that doesn't actually end in, "The answer is..." Right. And we don't really appreciate how incredibly transformative having all the information accessible is, but VR is changing that. So, we're gonna go from an internet of information to the internet of experiences. Wow. And experiences is a whole 'nother thing. For sure. So, that's gonna be the new currency, the new unit, the thing that we're gonna share, develop, trade, buy, invent, create experiences. How good? How fast? Maximum, I believe, is that we tend to overestimate the effects of technology in the short term and underestimate the effects in the long term. So, I think there's gonna be a little bit of trough of disillusionment right now, 'cause I think there's gonna be a few places where this is gonna be taken up this year. Games. Of course. Okay, but I would say three years, you should really expect to have those prices come down even further and you can at least try it and spend some money on it. There's a couple little places where, right now, it's gonna start, and gaming is obviously the main one. So, I think I read something you were talking about, that it wasn't tracking on Moore's Law, and that it's not really exponential. You still stand by that? That was AI. Yeah, okay, that's fair. That's AI, and so AI is part of VR because a lot of the stuff needs AI to kinda figure things out, but AI is what was not exponential. But VR is starting to happen pretty quick. Here's how I would say, here's kind of the summary, the bottom line. The bottom line is that VR is now real enough to improve. It's good enough to improve at this point. Before it wasn't really there. There wasn't enough even to make it. Cobbled, yeah. But now there's enough that it's gonna start to happen really fast. So, maybe not this year, but it's gonna improve on an ongoing basis very quickly. Law of accelerating returns? I think, is that what it is? Exactly, increasing returns. Yeah, when they were working on the human genome, and it took one year for the first 1%, and they said they were gonna have it done in 15 years, yet they actually were on that timetable because the technology accelerated over that time period, right? Right. So, actually, even at South By I saw another demo that really blew me away, and that was... Was it Meta? I've seen Meta, but this was a capture, a technology that captures, like, us right now. Sure, three-dimensional mapping. They would have 12 cameras in here and they would be capturing this, and then when you put the goggles on, you would really think that you were sitting right here and you were talking to me. You would have absolute convincing that that was really there. (Chase laughs) But that's a lot of processing. The high-end is gonna be in making those kind of games and things isn't gonna be something. But, eventually, you'll be able to, with four friends, take your phones, and four of you could set up and hold your phones and we would be able to capture something, mother, first steps of baby, whatever it is. That'll come. All right, so, confession, my career, my professional career, the whole time I've been an artist... I started CreativeLive in 2010, and it's been a hell of a journey since then. However, my background is actually in philosophy. I dropped out of a PhD in philosophy. And one of the things I was interested, I was primarily focused on the philosophy of art, judgments, creativity, but very intrigued by the philosophy of technology. And so I'm intrigued, and it was that connection that originally pushed me to follow your work really, really early on, and specifically Wired Magazine. But talk to me about the philosophy of technology. Rather than thinking of actual modalities, or like, talk about first principles for a second. Because the creative mind, I think if we're better at grasping principles, then we can do more with them. So talk about... That's a good way. That's a good way to do it. So my last book, not the coming book called The Inevitable, which is about all these trends, VR. June 2016. 2016. We'll plug that thing. The last book was called What Technology Wants. And it was the first theory of technology. 'Cause biology was sort of just one thing after another until the theory of evolution came along and unified it. And technology these days is sort of the same thing. It's like, well, there's this, and then there's that, and then there's this. How are they all together? And I'm suggesting a theory. And one of the things I would say, just to kind of bring to the philosophy part, is that I think that the origins of technology goes back of the big bang. It's not just about us humans creatively. It's actually part of a very long self-organizing system that will work in the past, is working through us and will go beyond us. But the important thing is what we get from technology is that we get increasing choices. Every new technology will create most of the problems for the future. All the problems we have today are from technology in the past. Today, we're creating technology that will make all the problems in the future. It was like, what do we get for that? Well, we get one thing, which is we get increasing numbers of choices and possibilities. And so, even though you may be working on something technological that may seem like, oh, this is just consumer. People are just... You know, they're just buying stuff that doesn't last very long. It's obsolete. It's maybe just getting people to click on ads. Whatever it is, it's more important than that. When you are making something, you're actually participating in this very long trend that went back to the beginning of increasing the possibilities in the world. And imagine if Beethoven had been born a thousand years before anybody invented the piano or the symphony. What a loss to us that would have been. Or if van Gogh had been born before we invented oil paints. What a loss to him and to us that would have been. Or Hitchcock before we invented films. What if he lived a thousand years before that? So we make these new technologies which enable their genius to be shared with us. So that means that today, somewhere out there is a young person who's waiting for us to invent the technology that would let them shine. Their genius is waiting for this technology that we need to invent right now. And so part of what we're trying to do by inventing all this stuff and making all these things is to fill out these possibilities so that it could liberate and unleash the genius of anybody in the world. Do you know the work of Michael Meade? I don't. He's a, gosh, I don't know what Michael would call himself. But he's, the term genius, it's, you know, part of the name of the series. You brought it up. And I think that at CreativeLive we talk about, creativity in embedded in every human being and it's just our decision, our deciding to work on this, to elevate it, to point a flashlight on it. And the same is true with genius. And Michael Meade talks about genius being when you're aligned with your true self and all of this stuff can sort of flow to you. And, you know, it's a huge thing for the people that are watching, for the fans of CreativeLive, is there's sort of a whole posse of people that consider themselves creative, and they're going on about their world trying to make new things and invent these things that we're talking about here. And there's also the people who are sort of dormant or they need to go from zero to one. What would you tell the people who need to go from zero to one who want to start making or maybe advance their making, their creativity? How would you fit that into your philosophy in unlocking genius in anyone? Right, right. So I think... There's a story that I really like, and I may have told it before, but I read it in a great book called Art and Fear. Oh, yeah. Okay. And the story's basically about... I mean, this... Steven Pressfield. There's two authors. Is it Fear of Art? Fear of Art, yeah. There's two books. This is a very difficult process to kind of find your way, and, you know, there's no going A to B. You go this way, sideways, back a step, detours. That is what you can expect. That's all that successful people do. And so it's a very difficult thing. But the only way that I know to make all of these trade-offs between making something that is understood now versus appreciated later, that can sell now versus appealing to you, all these trade-offs we have to make. The only way that I know that gets you through that even when you're beginning is basically to do lots of it, to do it again and again and again, that 10,000 hours, whatever it is. And the story was there was this art teacher, this ceramics studio art teacher, and he gave his students a choice of being graded in two ways. In one way, he said, you can submit one thing to me that you work on all semester, and I'll grade you on that. Or, he says, if you don't feel that confident in what you're doing, just make a bunch of stuff and I'll weigh it and I'll grade you on how many pounds you made. If you make 50 pounds, you get an A, whatever it is. Okay? So, that was an interesting thing, and kids did it in different ways. Fascinating. But here's what the brilliance is. He said, inevitably, every year, the best piece always came out of the group that did lots. It wasn't the group trying to perfect it. It came out of the group who had chosen to do as many of them as possible. They always made the best piece. I think yeah. Doing something instead of nothing is like... But doing a lot of it is the key, is what I'm saying. The only way you can figure out is to make as many mistakes as possible, to just keep doing it, and that's the only way to get through all these little bottlenecks and stuff, is you have to keep doing it again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again. That 10,000 hours of deliberate practice, not just practice, but with deliberation, meaning that you, deliberate practice is defined as you're actually trying to do something that can fail. Not just doing it again and again, but you're trying. So you're trying for 10,000 hours. Yeah. We have a... Call it a class, a series on CreativeLive called 28 to Make. You press that button, you get 28 prompts, one in your inbox every day. They say it takes 28 days to make or break a habit. Sure. And then people, again, submitted, not unlike what we're doing here with 30 Days of Genius, we had more than, I don't know, tens of thousands of hashtags. So that would be at 20-something-thousand people from 100 countries doing this. This was just in February. I mean, stunning, some of the things. And you can see transformations from day one to day in a single person's work. And it's just the act of literally, yeah. Doing it again and again and trying. Yeah, doing it again. Trying. Yeah, the try. It's not doing it. It's trying for it. Yeah, you're not gonna close your eyes and scribble. All right, so that was a little intellectually heavy to go straight to the philosophical stuff. I'm happy to do it. It really fires me up. But I'm going to flip the script here just for a second and go... It's not not heavy, but it's the thing that I said in the intro to the show. The 1,000 true fans post was hugely influential to me. What year was that? Do you remember? 2003 or 2004, something in there. I started writing a blog, a personal blog, at chasejarvis.com/blog, and I've started making videos. There wasn't even YouTube then. There was this thing called Google Videos, terrible. And I remember the idea that I was a, I would call myself a successful photographer at the time. I didn't know where I could take it. But I was already intimately aware of the relationship that I had or had to have with commercial clients. I was shooting big campaigns for Apple and Nike, and when people started paying attention to what I was doing and writing and saying and sharing, and I was cognizant of the following. I was not doing anything to build that following, because the concept of building an audience, it didn't even exist, until I read your post. And it was like, wait a minute. This could or would equate to some freedom that I, you know, that I typically wouldn't get. And now there's all kinds of like... I also have a little fine art world that I've been working in, and even then, rich patrons, they, you know, there are some sort of guidelines. And not that I'm looking for no guidelines. But freedom, that is a very valuable. Give us a little background. What was in your mind when you saw this? 'Cause you clearly projected... I mean, Kickstarter is something you projected 10 years before its time. So what was some of the key sort of markers? And then we'll go into talking about how people can... You've revised that a little bit since then. Right, so the basic idea of 10,000 true, excuse me, 1,000 true fans was the idea that with technology, again, I'm big pro-technology, I think technology does so many things, that with this new technology of having direct contact with your customers, that the calculus of how many customers you would need to support you shifted. So, I did a, kind of secondary to this, I did an examination of what it took to make a hit in all the different media. Got it. Like, a one time... So I did this... I took the 40th. What's the 40th most popular thing, whatever it is, on the radio, a song, a book, and how many copies or things did it need to get to 40. And it was shocking. Like, books. You could get on a bestseller list selling 10,000 copies. And so I began to think about, well, what would it take if you were not going through the publishers, 'cause they're taking most of the money. But if you could have direct access to your customers, what's that number? And then I was just doing kind of a mathematical calculation. Well, if you could have true fans who would buy whatever you did, who will come wherever you were singing, who would purchase each version and edition of whatever it is you produce, whatever it is, if you have true fans and you could sell them $100 worth of content or creation a year, then you could maybe get by on 1,000 of them. It'd be 100 grand. 100 grand. You could probably do that. So, even if that number wasn't correct, the order of magnitude was kind of there. That's not like a million. You don't need a million people. You don't need to be platinum. You don't need to be out there. You can do something in a much more reasonable scale. And so, there were changes if you have more than one person, et cetera. But the idea was that this new technology allowed us to be on a scale that we hadn't done before. Because 1,000 true fans, you could kind of almost know all the names of them. You can almost kind of see that in your head. And those of us that have larger followings, I recognize people, and there are people going to me like, I'm Sammy Smith! Like, Sammy, you've been following me for years! Great to meet you. Right. And that's just the true fans. Because then there was the kind of, the lesser fan that would still maybe get some of the things you did a year. So you could actually make something around that. But, the but is that you have to directly interact with them. And there are artists who don't want to do that. They're busy. They say, I wanna make art. I don't wanna deal with them. I'd rather have someone else do that. That's fine, I'm just saying. But if you are willing to do that, if you were to take that and enjoy that and are good at that, that is a path. And you don't have to reach for a million. You can reach for a thousand. And a thousand is something you can imagine doing, you know, one by one by one over a number of years. You could see that. So, that's the idea. I love that idea. Let me tell you the way it worked for me is, and I think this is, it very closely ties to what we were just talking about about the practice. Like, I can envision what it means to have 1,000 true fans, and so what did I do? I did the work. And I started building and making and sharing. I called it create, share, and then like, sustain by doing whatever you could until the time where you'd have 1,000 true fans, and those thousand fans came so fast, because it was, I looked at how achievable it was, and definitely what I'd like to go to next is how to leverage technology for artists and creators. But it was reasonable. It wasn't like, oh my gosh, do I need to be the next Cartier Bresson or whatever, you know, whatever photographer or designer or entrepreneur that you aspire to be. I just needed to go to work. And in that work, I found great joy. The amount of pressure that I put myself on, and I think this does go for people, even if you don't want or don't aspire necessarily to make all of your income or to make a life around this stuff, but just, as a cycle of feedback, it just made it within reach. And I found that in doing that, not only was I creating a potential net for myself, but I was creating community. 'Cause there's this relationship with the work I was putting out in the world. So, you said you're a technologist or a futurist, and you like how technology. Can you talk to me about what you think, what's the next 1,000 true fans, or how should people be thinking about technology? Is it, the same thing applies, or has that evolved? Well, so, when I wrote that piece, I was... 12 years ago. Yeah, I was looking around for actually, for people who actually got funded that way. This was before Kickstarter. Kickstarter was not the first crowdfunding site. There was a couple sites that were experimenting with that. So obviously, having your fans finance and fund your work is brilliant. That is a technology, and by the way, you know, there's lots of different platforms. There's almost 400 platforms worldwide. There's platforms that specialize in musicians or filmmakers. There's one who do, like Patreon, who do ongoing processes. There's lots of them. They're very powerful, and you should really, really consider them. It's a brilliant way to kind of make this work. So, are there technologies beyond that? I think there are some technologies we haven't yet invented that we will invent or need to invent. And that is, and VR may have some role in this. And that is ways to collaborate, socially collaborate, to work with either other people or even with your community and to have true collaborative tools. So right now, as we all know, it's often easier to make something when people are around together. I mean, that's just the... You have people to bounce stuff off of, yeah. It's the serendipitous thing. It's like, you know, at Wired, I would spend, I only go in for half a day. And I made it very clear from the beginning of this, is that I said, you can have meetings any time you want, but I'm not coming until 11. If you want a meeting, make it in the afternoon. And so I would go into Wired for only two reasons, into the office: to have meetings and to be interrupted. If you wanna do work, I'm going to be working at home. That's where I'm going to do stuff. So I'll come in, but only for the social aspect of it, just because you want to have the interruption. You want to have that serendipity. You want to overhear something that someone else is talking about that they didn't think to let you know, but that's how it goes. I think some of those tools, allowing people around the world to actually collaborate and work together is going to be the next big thing for the creative community. That's very powerful. You know, we tend to honor the lone genius, but believe me, most of the stuff of the world, this program is not just you. I know. Turn the camera around. (both laugh) I'm as much a problem as I am a solution. I promise. So, it's really, really, I think this is a very powerful thing to do that will again, bump up, I think, the creativity. Which I am, you know, I'm just very impressed by. It's not just... I mean, you can't go onto YouTube and not be amazed at what is happening in the world of creativity. And it's because of this really fast cycle. People make something, they put it up, they get responses, and they inspire somebody else, and the rate of creativity is just astounding because of this new technology. I think the next big level is really having really collaborative tools that work in existence. That is powerful medicine. When, gosh, so if collaboration is a huge key to the future and you think technology is gonna enable that, talk more about the face-to-face, like, why you went into, and I love the term that you used, interruptions, because that tells me that someone else is having an idea that needs to get out. And, you know, we can talk about whether that's the stroke of genius, not Genius with a capital G, genius with a small g, but talk about that for a second. Okay, so here we are, South By, this huge place. People from the creative industries, the digital world, the VR world, they're coming face to face into this one little city and bumping into each other. That, we know, will increase. And so this is back from my days when we made the first online community. It was called The WELL in 1984. One of the first things we discovered besides these amazing, real communities, real virtual communities, was the fact that it increased everybody's desire to be face-to-face. Like, the Sammy thing I was getting at earlier. I was like, hey, I wanted to meet you! Great, yeah! So that's not going to go away. I think what we do is we just add other ways to meet in addition to face-to-face, and often, that other ways will encourage us and compel us to also meet face-to-face as well. So, I think both of those things don't take away. So I imagine... It's additive. It's additive. Technology is additive. It doesn't take away. You can still read books. You can still use books. Books in some form, may not be on paper, but the kind of narrative will still be there. But we'll have other ways. And that's the real beauty, is that we increase the choices. We increase the possibilities. So we'll have still face-to-face. Conferences will still be important. But we'll be able to collaborate with people in South Africa and someone else who has our same fascination with saltwater jellyfish, and we're going to, you know, we're going to work. There's a community for everything, yeah. Exactly. And we're going to work together on something that we couldn't do before. You talked about sort of maybe two modalities, one of going into work and being social, excuse me, and then the opposite of that, staying home, which let's get out of the theoretical for a second and get into a little bit of you personally. So, you protected your time in the morning. I do the same. Militant might be a little bit of a strong word, but I'm very protective of certain pieces of my day and certain elements of my time. I would like to know that about you. If you didn't want to come into work before 11, is it 'cause you needed to sleep in? Is it you work so late? Is it because that was prime working? Did you have some regiment in the morning that prepared you for the rest of the day? Yeah, so, it changes a lot for me, because I have, you know, three kids, a working wife, and so we have patterns now that are a little bit older. Or they are older. They're not in the house. That changed. Secondly, I was working at Wired, which was a very collaborative workspace. So now I have an office adjoining my house. I have two assistants, and unfortunately, my office is attached to my bedroom. I don't recommend that. I knew that before, but it was the only way we could get it onto our property. And so, I have become pretty good at saying no. I think you have to become really good at saying no. And I learned a lot from my mentor, Stewart Brand, who was really good at saying no. And he always said no in a way that made it seem like it was a favor to you. I wanna get this before we go, but keep going. So, you got good at saying no. Right, good at saying no. And so, so, I don't have a ritual for the day. Lots of days are very, very different. I still do a lot of travel in Asia. So I may be gone for long periods of time. And then I have different kinds of... So I'm a very project-oriented person. I have projects that I'm working on. And those projects sort of dictate my day. So I've been mentioning I was writing an article for two months for Wired. So that was, I was going out for interviews, doing travel, so that was a very different kind of time when I may be working on my next book, which is a photography book. And so, that's a little, that's a little different. But the saying no part is during that time, I reply to every single legitimate email that comes to me. My email's been public for 35 years. And so I respond to each one. But I will very easily say no to things and depending on the project and my time. And so it's like, no, for this time I have an auto-reply saying I'm on Dillon. I can't do anything more. In addition, I take your thing seriously, whatever it is. It sounds like a very gracious no. And that goes out. And so, then I'll work. But then I'll be in another period, like when I'm promoting my book, which is like, I'm saying yes to everything. Everything, yeah. Everything's yes. Sure, why not? Okay. Stand on the street corner? Sure. Exactly, one, two, three. Okay, so, so, it shifts. And so my day is really much more project-oriented. But there's, while I'm home, there's one thing that I do have a little ritual that is an indulgence, and that is I still get the paper edition of the New York Times, and I sit there. You sit there, you smell the ink. And, you know, while I have breakfast, I look at that, and it's like, there's no reason why. I could get everything on the internet. But it was just sort of like this one thing in the morning. I don't know why. I just enjoy it. And did you carve your morning out just to read the paper, or did you carve your morning out so that you could do other things that were the biggest things that you were working on at that time? No, I'm not, I'm not that deliberate in structuring. As I said, things vary. I'm not a very good planner. You know, there's people who have their day up, pretty much schedule it. I have never been that. That's not my personality. I'm much more, I don't know, I have in my mind things that I need to do and I kind of get to them, but I'm easily bumped with things. And for me, like, you know, if there's a, you know, there were barn owls nesting in the tree next to us. Oh, they're having babies. I need to see this, whatever it is. So I really tried to be a little bit more available for those kinds of things that are happening, and I think those are, to me, as important as, you know, as long as I get the work done, as disrupting my day, anyway. Incredible. Let's talk about your book. The photography book? No. I definitely want, I actually don't wanna disrespect your next book. So I'm dying to know about the photography book, given my background, obviously, but let's talk about The Inevitable. The Inevitable is being published by Viking Penguin, and it's about the next 20 or 30 years in technology. It's the large forces that have been running for 20 years already, and they're going to continue. And that's the inevitability. It's that soft inevitability. Moore's Law and... It's not Moore's Law. It's, I have 12 verbs, 12 forces, that I think are going to be increasing. So, one of them is cognifying, cognition, cognifying, the idea that we're going to put AI into everything, and AI's going to be a commodity that you buy and it will flow like electricity into anything. Here's a formula for the next 10,000 startups out there. Take something, add AI that you buy from Google or Amazon. You can now buy AI from Google for 60 cents, 1,000 impressions. So Google, all these big companies are going to sell their AI stuff, which will flow to you like electricity. So just as in the past hundred years ago, people took things and electrified them, took the pump, made an electric pump, took the car, made an electric car. Now we're going to take take things and make them smarter, make them cognition, and that is going to be very, very powerful. So it's not really about making. This is one of the philosophies of technology things that I was wrestling with quite some time ago actually is like, okay, if machines are getting smarter, let me just do the math, and okay, but if it's the things that we're going to benefit from, not AI in and of itself, I think the best analogy that you just used is electricity. Electricity powers all the things that people are inventing. We don't need that many AI systems. Like, we don't need that many... We got AC and DC, and we got a couple of basic currents of electricity. Is that how you think about it? So, a lot of the work that we want done in personalization is going to require kind of the AI backend. So, let's say in your own business, you're issuing helpful instruction. What if it could be personalized in some ways, that was very really truly personalized? That would require in some ways a degree of kind of attention that maybe a human could give to right now, but that doesn't scale. But you could scale it with AI that you purchased. You're not going to generate it. It's much too complicated. You're just going to purchase it. Don't engineers want to build everything? Right, right. You're going to just purchase it and put it into your backend. And, so, another way of thinking of it, you could actually flip it around and say if AI is a commodity, then you take AI and add x. It's sort of like, it's going to be, what do you add extra to the AI. Yeah, what's the x? What's the x? So that x becomes important. And it's sort of like, but that is really how big. So that's an example of the inevitable that I'm talking about, that it's going to get smarter and smarter and think of it as artificial smartness rather than artificial intelligence. Because people get really hung up on the intelligence and it's like, weird, and, you know, it's the Terminator and all this. You know, forget that. It's industrial. It's boring. Electricity. Yeah, it's just electricity. It's just synthetic learning, synthetic smartness that you can purchase and put into it whatever you want. Give us one other example, if you can, of another one of your verbs, one of the 12 verbs. Yeah, so another one is tracking. Data. Data. Everything we do. Quantified self, which I started with Tim Ferris and others. Tracking, self-tracking. We're going to track each other. Corporations track us. The governments track us. There's no way to stop the fact that in 50 years from now, 100 years from now, most of our lives will be tracked in some capacity or another. And the question is, it's like, we can't stop that, but we can civilize it. We can make it symmetrical. We can make it comfortable. We can, in some ways, redeem it, but we can't stop it or prohibit it. You can't go backwards. I'm a fan of Snowden, not because I think he's going to stop the spying, but I think I wanna make it transparent and so that we benefit from it, so we get some benefit. He's been a powerful figure obviously in the last 10 years, five years. Right, right, right. One of my favorite... I've heard some talks with him, live talks, and one of my favorite things is like, do you wish, it's not whether or not I'm a traitor. It's do you wish I didn't know what I told you. Yeah, no, I think he's a hero. He's a hero for me. So, that's the idea, that we're going to be tracking, what can we do with it and how do we make sure that it stays civilized and virtuous. But my point is that that's inevitable. There's going to be more of it. And there are 10 other inevitables that we have to get your book. Well, so, like screening, this idea that, and this is maybe pertinent to what you're doing. I think there's a movement in our culture which, we were people of the book. So our western society is built on books and writing and core texts like the Constitution, like the Bible, like laws. We had authors. We gave them authority. So, we were, we were based around the book. And now we have become people of the screen. And so the screen has a different kind of a logic. There's no authority in the screens. You don't have authority. For every expert, there's an anti-expert on the internet. For every fact, there's an anti-fact. And so, we actually have to assemble our own truth, and we have to be much more involved and engaged in that, in critical thinking, all this kind of stuff. We can't just get things from authorities. So books are unfinished. Wikipedia is kind of continuous. So there's the fleeting movement on the screen, which is a very, very different kind of world, and the text had all kinds of things from the Gutenberg Revolution, like the table of contents and index, glossaries, abstracts, summaries, that we don't have yet for moving images, tools for us to kind of unbundle things. The thing about authors and text is that we use found elements. It's a closed dictionary. I don't make up any of the words. There's no such thing as a private language, right? I take all the words that other people have made, and I remix them. So remixing is the other verb. I remix those words into something that's new. We want to do that with the visual, but we can't, because they don't unbundle right now. But with AI and some of the new things coming, we can actually extract out different parts of a video thing, take out those parts, remix them, and we're beginning to see that with like supercuts and other kinds of genres where they are going through, taking a corpus of existing things, and remaking them. It's still very, very difficult, but we wanna be able to like hyperlink from here into the moving frame of a hat inside a particular sequence of frames. We can't do that yet, but we will. And so, as we kind of bring the Gutenberg Revolution to the visual world, that is going to be the new media landscape. That's going to be the place where tremendous creativity, tremendous wealth, that's what the new media companies are going to be in, is in this shift into the visual component. I wanna, I'm putting a pin in so many things in my mind right now that I wanna hold onto. So, inevitable. We should put a nice graphic of that on the screen right now and encourage, they can probably pre-buy it in the not too distant future. Yes, it's pre-order on Amazon right now. Okay. It comes out in June 2016. So there's the photography thing I wanna talk about. I'm also interested in, well, actually, let's just go to the photography. Photography is so... So, here's the thing. I write. I hate writing. I love having written. (Chase laughs) But I hate writing. It's just painful. I'm a born editor, not a born writer. But I love photography. That's how I started out. I dropped out of college and I was a photographer in Asia. When I'm photographing, I'm happy when I'm editing, processing, like, I could just waste... I'm in the flow state. That, to me, is just what I love. That's breathing. And so, I did a book for Taschen. I did a book of photography for Taschen called Asia Grace, and it was my work in Asia, and I'm now doing another one that's even bigger and crazier. Wow, also with Taschen? Well, the way I did it with Taschen, and this is... Another model for us here? Yeah, there's a model. So, I did this photography over decades. I was working towards the book. I wanted to do a book. But I was a nobody in the photography world. And doing a photo book was this huge thing. You needed to kind of be a big person. So I waited and I was waiting until the tools came. So it Quark, at that time. It was basically InDesign and Photoshop. So, I scanned, I had all the very early, scanning all my slides, and then I designed the book myself, color processed them and designed the book, printed it out, and I mailed it to Benedikt Taschen cold, and the book was ready to be printed. Awesome, wow. And I said, here's the book. Do you wanna run it? And he looked at it, and two days later he faxed back and said absolutely, we'll just print it. (Chase laughs) So that's what I'm going to do again, is I don't want to get permission. I'm just going to make the book and design it exactly how I want it, have everything done, it's camera-ready, and say, do you wanna print it? And if they say no, then I'll print it myself. I've done a couple of self-published books, a huge graphic novel and another Cool Tools book. I printed it in China. We sold very well on Amazon. So, that's another thing we can talk about, self-publishing. It's real. It works. You can do it. But, I think the tools are the point, is that the tools now allow you to have a lot more leverage and to go further along that process. I could not have done it in the past. Sure, there's more freedom now than ever before. The gatekeepers, for the first time in the history of the world that as creatives, we didn't require permission from the gallerist, the publisher, the editor, to get our work out there. But there's a lot of work involved. That is the barrier, I find, that's actually every bit as powerful as the gatekeeper. Right, so, you know. 'Cause who's willing to do the work? Who's willing to do the work? So, Cool Tools only took us about, you know, 12 years to make. I worked on a graphic novel that was really great. We worked on it for 11 years. There you go. (both laugh) If you're willing to sign up for it, everything can be yours. Exactly, right. So, the photo book that I'm working on is the first book. We're recording the disappearing traditions in Asia. And, you know, it might be classed as street photography, in that sense, and that's what this next book is. So I'm still going to back to Asia and to the places where there's still some remnant of a very timeless scenes and I'm capturing those before they're completely gone. And so that's, so I have these little pockets of them. I'm headed back to, trying again and headed back to Kerala in April for the elephant temple processions. So I'm kind of gathering the last bits. And that's, that's what I do. That sounds like a beautiful project. I hope that you'll let me see it early. Let's talk about the philosophy of photography for a second. So again, I'll pretend or assume that you don't know anything about my background, but I helped popularize the phrase, the best camera is the one that's with you. So, if you wanna see me, if you wanna see my cameras, I never have never bought an SLR. I never, I mean, I've never bought the state of the art. I was too poor to afford Nikon, so I had Nikkormats. I had Nikkormats, and the first one was a Pentax and Nikkormats. Then I was shooting with, believe it or not, I was shooting with Costco, Kodak film, Costco processed film. Then I had point-and-shoots for a while. I was actually shooting with little point-and-shoots, and now I use what hey could call super zoom, on a Panasonic Lumix. They're a good camera. I know, but they're way, I mean, they're cheap. Super cheap. Super cheap. So I've always gone with the super cheap. So I, the same thing. The best camera is what you have with you. I also parrot Lance Armstrong, 'cause Lance Armstrong would always say, it's not the bike. So true. And I always say, it's not the camera. I've got a great video online of me shooting with a Lego camera. So if you're really looking for some entertainment, it's, there's humor behind it. I'm 100% there that, you know, and then by the way, the other thing I would say is, I would never in a thousand years... You could not ever pay me to go back to film. Brutal. Never, never. Terrible for the environment, slow, awkward. I mean, I can't even begin to tell you. 'Cause I had 500 rolls of film in my backpack, 500 rolls. No clothes, just 500 rolls of film. And the biggest downside was, you know, I'd expose them, and then I was gone for very long periods of time, and I would mail them back to my mom, so she'd put 'em in the freezer so that when I eventually would come back, I had to earn some money to be able to process them. So the delay in the feedback loop of seeing what I was shooting would be months, many months. That's terrible. That's terrible for learning. It's terrible for learning. It's terrible for professional. And so I would even have to, every month, I would buy a roll of black and white film locally and send it through the camera to be sure that my cameras were still working properly. I did the same. I had always aspired to be a photographer, without going into the nitty gritty details. Was trying to reconcile my personal identity around it. My grandfather died days before my college graduation. The silver lining there was I got his cameras and went and decided to walk the earth for six months with my then-girlfriend, now-wife Kate and taught myself how to become a photographer. Everything you just talked about walking through Asia, I had walking through Europe, spending all my money on film, not knowing if the film that I was shooting was actually, so we would have to save up. We would literally eat a can of beans for a day or two and save up enough money to then process the film, and in Europe, processing film is super expensive. And it's like, great, okay, there's something there in the camera. And learning through taking a picture, writing down your exposure, exposure one, f/8, 1/250th, click, and then looking at exposure one when the film came back, you know, x days, weeks, months later, and trying to learn like that, it really undermined the learning curve. There's so many other reasons why digital is better, and for me, this is a very obvious one that has really made a huge difference, and that is the fact that there's a silent shutter, at least on the ones I use. I use ones that don't have the click. And because of the kind of photography I do, which is a little bit invasive. I'm in, you know, I'm trying to capture kind of all candid, nothing is lit or anything, controlled light, in settings where I'm so fast that they don't even know I'm taking pictures or they're not even obvious. And so that was a huge thing for me, was just having the silence. Instead of the... An old Hasselblad. Kerplunk. So, that's the kind of stuff I'm doing. So that, for me, was another big benefit. So, when I start shooting an iPhone, I was, I shared this earlier before we started recording. It was vilified. Like, as a professional who's traveling all over the world shooting for, you know, Fortune 100 brands, I found, and it was actually the Palm Treo where I started taking pictures, a sub-one megapixel camera, and then when the iPhone came out, I started taking pictures with it. And I was like, what are you doing? This is so horrible for industry. Anyone can become a photographer, and I said, well, wouldn't it be interesting if, instead of 60 million photographers, if there were six billion photographers. And, you know, the idea of having a camera, and what is the proliferation of the image? Let's not only think about our narrow, myopic profession for a second. Let's think about the future of the world. So how do you see photography impacting the future of the world? Clearly, I mean, my philosophy is very much visual. You know, a thousand pictures, a thousand words, so what I love about a photograph is it's a language that is universal, that's almost instantaneously consumable. How do you think about these things? So I think where this is going to go is that, I'm not sure what the timeline is, but I think it's in the short-term, is that we'll have VR capture. We'll have not just stereo but a VR capture. And that, again, feeds into this shift from the internet of information to the internet of experiences where we are really putting people in that space that we're trying to capture, that moment. And it'll be much more visceral. And I think that that's gonna be a part of what people are doing with their little devices, not just a flat kind of glimpse, which will still happen, but also trying to, in some way, capture something even more. And the weird thing about trying VR is that there's a shift from, what I call from first-person to you-person. And when you do, like in a first-person shooter game, you're kind of shooting there, there is a sense in which you are kind of watching that. Sure, it's still over there by the bookshelf. It's still over there. But when you're in VR and doing it, this is not something you watch. This is something that you are there, and you remember it as something that happened to you rather than something you saw. And so, that sense of moving it back into the you is what you gain by the virtual reality. And I think if we begin to have these, if the same progress is where it's now just kind of flat but it moves into much more of a kind of capture the whole thing and we can move ourselves into that, I think that can be very, very powerful. And a lot of the same kind of thinking about framing and all those things that we have with photography will still be there, plus others that we have to think about which we don't have. So in film, we have the establishing shot and we have cuts and closeups, and we know what they mean, but they took actually years to develop. We don't even know what that is in VR. Yeah, the vernacular and all that. The syntax, we don't even have. I see so much, there's such a lack of context around this stuff right now. Oh, great, I'm watching in 3D. And, you know, at CreativeLive, we've done, you know, VR in the class. World-famous photographer shooting, put a VR camera in there, and the thing, that's not useful if it's 10 feet away from its subject, and you go, okay. If you put yourself in that sort of seminar, learning environment, physically, would you constantly be looking around? No, you'd look at it once or twice, and you realize that there's not that much interesting stuff going on over there. It's really right here. And so then, you know, VR at a 10-foot distance, that's probably not the best way to see these applications. No, the VR, the whole thing of VR, where it really works, is within your arm's reach. And it turns out that your arms or hands are 50% of the experience. So VR without any hand motion is like, you're not even half of it. It has to be, it has to be manipulable. It has to be within reach. You have to be able to move around. You have to interact. That's what really gives it. So I think that will be another kind of thing that we have to learn. It's not going to be just about images. It's interesting watching an old medium try and get applied to a new... Exactly. I think we're back in the Daguerreotype. You know, we're back in the early days of photography when nobody really knew anything. It's going to take us a while to figure that out. For certain. So, I'm not sure of many things, but I am sure of the proliferation of images and imagery. Yes, absolutely. You talked about screens. Is there a negative... Again, the way I talked about it was, when people would say, oh, man, so, film is dead. Well, film's not dead. It's just you have to be weird to want to use it. But it has its own place. Maybe in young students, it creates a sense of moving more slowly and, you know, more intentional compositional. Absolutely. But it's like, do you really wanna paint with oil paints now when you can paint with acrylics and it can dry... Yeah, 95% faster? Or you can paint VR, have a creative masterpiece before your eyes. What's, I guess, with imagery, I know it's going to proliferate. Is there some negative to that? Are we losing writing? Yeah, exactly. So I made a little hint of it earlier, which is this moving from people of the book to people of the screen, and it's the sense that we're losing experts and authority. And that is not an easy thing to lose. Because understanding what is true, it becomes more difficult. It is something that you have to actually work a lot harder at, and you have to have the skills. So I believe in a thing called technoliteracy, which is, there's a certain number of skills that we're not going to learn just by hanging out in technology. You don't learn calculus by hanging out with math books or whatever. You actually have to try and study and work at it and driving a car, you have to actually train. So I think working with technology and learning some of these skills about critical thinking is not something that is going to be done just by being online. I think you actually have to train to be taught it and how to assemble, extract out, understand how things work, to get your truths, plural, from this. And so that's a downside. And there's the ephemeral nature. I mean, a book is fixed and monumental. It's done. This other stuff, the screen is forever changing. It's ephemeral. There's life streams. There's this time component that is very different, and that's a challenge. There are negative involved in that. There's downsides. The negatives that you talked about. We're creating the problems of the future today. Exactly, right. And so I think there's going to be 49% of the stuff that we're doing is terrible, it's harmful, it's bad, but 51% is good, and it's that tiny delta, that two percent, that we compound every year. That's where civilization is at. So it's true. If you look around and you say, 49% of this stuff is terrible, you're right. Climate change, very real. Very real. We've gotta figure it out. Climate change, endocrine disruptors, I mean, there's lots of really bad stuff that we're doing, and I think the distraction that people talk about, it's real. You know, all of these things are real. They're real things. I'm not sliding it. I'm just saying that when we stack them up, that there's actually two percent more good, whatever that number is, I don't know, that will propel us forward, and that the, here's the second thing about that is, is that I believe that most of the solutions to those problems is more technology, not less. So, I make the analogy, talking about the philosophy, is that technology is like ideas made real. So if I was to sit here and give you a really stupid idea, you're not going to say, hmm, Kevin, you need to think less. Less thought. Stop thinking. No, you'd say, you need to come up with a better idea. So the response to a bad idea is a better idea. The response to bad technology is not less technology but better technology. And so, I'm very technocentric in the sense that I think when we have a problem, the solution is going to be more technology, which will make new problems, and the response to those new problems is not less, it's more technology. So, we're all in this cycle. What we gain out of all of that is more choices, more options, which is why everybody is living in cities, because that's what cities are. They're little possibility factories. They leave their beautiful villages in China with organic food and strong families and strong certainty, and they come to the city, because there's more possibilities, and that's sort of where we're going. That is a beautiful thing. The story, the narrative, is a very beautiful narrative. You said, talked about technology and possibility. For me, the thing that, you know, we believe at CreativeLive is that creativity is the new literacy. So you can use words like innovation, technology. I like to think of it as creativity, and there's two types of creativity: creativity with the small c, which is like art as a subset of creativity, so photography, design, music, all these things, but that's really a subset of creativity. Creativity with a capital C is that all of these problems that you're talking about, even, you know, mechanical engineering is creativity or the wheel is mechanical engineering plus creativity. Electrical engineering plus creativity is electricity. E=mc^2. Very theoretical science is, you know, science plus creativity. So I'd love to hear a few thoughts of your on creativity as a discipline, as a practice, and the fact that there's all kinds... I think it's Mark Runco from the University of Georgia saying that creativity begets creativity. So literally taking pictures with your iPhone can make you a better brain surgeon, and unlocking all these, you know. Yeah, I believe that. So philosophize for me on that, if you will, for a while. Well, the one thing I say about the creative lifestyle, the creative impulse, is that, you know, 95% of the results of creativity are failures. And so, Derek Sivers, right, yeah, Derek Sivers is, you know, really inspirational to me in the sense of like, asking himself, how good was my failure today? It's like today, what did I try that didn't work, and did I try something that didn't work? And so, that's, to me, that's a real inspiration, to really strive for that, to every day try to do something that could have failed then. And so, so I think that's part of the process, and that acceptance of small failure. So you wanna fail forward. You wanna fail on an ongoing basis. You don't wanna have big disasters, which is what the Soviet Union and those did by eliminating... By having all this planned stuff and eliminating anybody who could fail, they all failed at the end. It's the same thing with evolution. Evolution's such a powerful force. It's because on a daily basis, making mutations and other things, there's small failures. They're not log-jammed into big failures. And so, I think that sense, and that's one of the big differences between the U.S. and China right now, is that China is struggling with its culture, and part of it is that there are two things that they're struggling with. One is in tolerating failure. The second one is questioning authority. And both of those things are kind of part of what's resonating in American culture that makes it so vibrant right now. But that's part of the lifestyle, is questioning assumptions and tolerating failure. I'm gonna shift gears, 'cause there's just some short direct answers, which you're so good at. I've listened to a lot of your talks. What are you afraid of right now? I think... Is AI? Like, you talked about AI. Should we have some doomsday thing, or is it... Yeah, so AI, so, I think there's legitimate concern about AI, and I think there's going to be a disruption in our patterns of work. And without a doubt, it also is going to change our identity. So I think we're headed toward a permanent identity crisis as to what are humans, what are we good for, what makes us different, and what can we do, and what do we wanna be? And that's kind of the larger thing, but I think there's also gonna be a disruption in like, you know, the biggest occupation in America, the occupation that has the most people compared to other occupations is truck drivers. Yes. Wow. That is ripe for big change. It's all driven, cars and highways and trucks. So I think, even though in the long term, it's inevitable and it's going to happen, it's the 51%. It's the 51%? I think there's a lot of the jobs that people are fighting over are jobs that humans shouldn't be doing and in 100 years from now, we'll just marvel that we allowed human to do that. A cashier? Counting money? That's not a job you should... Nobody wants to do that job. That's a job for robots. So I say, any job that you can specify, any job where productivity is important is a job for robots. Humans should be doing jobs that are measured in productivity. Humans should be doing jobs that we don't measure, that are wasteful, that are inefficient. That's what humans do. Creativity, as we said, is inherently inefficient. That's what we do. Any job where efficiency is important, send it to the robots. It's one of the reasons that I say that creativity is the new literacy. Imagine if we put the same amount of effort and time, you know, in the immediately post-Gutenberg world to make literacy because it changed the mortality rate, the birth rate, all these things, and it was an incredible boost. What if we put that same sort of intensity and intention around creativity, because that's the thing that will make you indispensable, is the ability to ideate and to do these things that are incredibly inefficient but very, very powerful when applied. Right, right, very effective. Efficiency and effective are very different. So I think that's what we're going to move to. The new work is work that is not measured in productivity, because anything that can be will generally move to the bots and automations and AI and robots. And so we're left with things that are open-ended. And so another way of explaining it is like you can think of the world of Google and AI. They're working on these conversational agents where you ask in complete, plain language about, you know, something, and you get a perfect answer back. So answers become cheap and ubiquitous. They're free. Perfect answers. What becomes valuable? Questions. Great questions. Great questions. Asking, what's a great question? There's so many ways a question can be great. One of the most important ones is it opens up new questions. But asking questions, that stance of questions, that is something that robots and AIs are not going to do for a very long time. That stance of questioning, the assumptions of questioning the framework, of questioning what is known, of questioning how you do something, that's the creative act. That's what humans are going to be really good at. And if you want to be creative, that's what you wanna do. Beautiful. How about another short answer. What's something that people don't know about you that you think would be interesting? Oh, boy, yeah. There's a Wikipedia which has all kinds of incorrect information. I just am eternally misquoted out there in the world, too. Right, exactly. There's things I didn't say and all kinds of stuff. Things that they don't know about me. Just a thing, a thing. You're going bananas. No, yeah. There's nothing really important, but I, I would say in general, I'm not a really high-tech person. Like, you know. Your day-to-day movement. Like, I'm really not very much of a mobile person, phones. The way to reach me is email. Not even texting. 'Cause when I'm traveling, I don't even have it on, and I don't have cell phone coverage at my house and stuff. That's amazing. The founder of Wired Magazine. I know, exactly. But this is the best answer. And is that intentional, or do you find that, like, there's just too much to learn all the time? Well, I'm sort of Neo-Amish in the sense of like, I'm very deliberate. Neo-Amish, yes. I'm very deliberate and not afraid to not use something. I will try lots of things, but I'm very quick to abandon them and say, I'm gonna just use this thing. And so I'm not embarrassed if I'm not using that. But I will try most things. That you've tried all of the VR. Right. But am I gonna buy VR? No. 'Cause it's too early. I think so. I can't imagine myself buying, you know, $1500 for an Oculus. What am I gonna use it for? So in that sense, I'm trying things, but the things that I actually bring home an use on a day-to-day basis, I'm pretty conservative. Because I discovered this amazing thing, which is like, each new thing you add to your life is, it's kind of like, it's not just the purchase price. It's the maintenance, the upkeep, the upgrades. It's like having a pet or something. Would it be the difference between, as someone who owns a little bit of real estate, the difference between owning and renting. It's not just the purchase price. It's all of the future maintenance and all of the headaches. Right, and so you get each time, and it's like, all that stuff, and then how it interacts. It's an ecosystem. It's like, is this gonna be friendly with the other stuff I have? And so, that's technoliteracy, in a certain sense. I think you have to be very, very selective in what you kind of adopt and use, and I'd rather kind of keep that time for other stuff. Is there anyone that you think I should, we've got a couple slots left in this series. Yeah, oh my gosh. I mean, and this is not intended to put a lot of pressure on you. So if you wanna punt, you can. But you have a sense now for who we're, you know, the kinds of things that we wanna talk about and explore, and there are people who are just literally making things everyday, designers, photographers, that I wanna look up, and they're putting out great work. We can learn from them. We can learn from someone at the opposite end of the spectrum, and everything in the middle. Yeah. I will have to answer that offline, because I do know them, but they're not coming to front of mind. I get asked that question. Like, who do I wanna throw under the bus, which of my friends? But for me, I think for me, my answer would be something that's, I like the kind of fringes. So I'm thinking of a guy who makes popup books, Robert Sabuda. They're amazing. You open 'em up, and these things just, a tyrannosaurus Rex comes out of it, and it's just all folded with paper. It's just like, amazingly engineered. And it's that kind of offbeat things that I sort of really enjoy, or, you know, some YouTube guy who's doing, you know, some innovation in YouTube. That's the kinds of stuff that I look for in terms of being inspired by creative. It's at the edges. That will help me in continuing to curate this series. Right, right. Magicians. You know. I find, I think going to the edges and looking at the edges, whatever business you're in, the disruptions and the outside, the disruptions will come from outside of your business. It's like, okay, in the car business, the disruptions aren't going to come from the GMs and the Fords. They're going to come from the Apples and the Teslas and the Googles. Whoever thought? You know, in the hotel business, it's the Airbnb's. And so, whatever business you're in, the things that are going to come over and really take over are going to come from outside of that. In photography, it's going to be something outside. The Instagram. Whatever it is, those are the things that you wanna pay attention to. So I spent a lot of time trying to monitor the edges and look out beyond the obvious things. That is literally how I've made my career in photography, is looking at the storytelling, that the meta layer of telling stories about making pictures and helping people inside the black box. That's definitely outside. There's an irony in that you're telling stories, but telling stories about the work. And that was a very big vehicle that, you know, you put that together with an audience and then influence and I can launch a campaign as a photographer and get hired 10x over someone else who is every bit as good or even better than me. Right. So if you were looking at stories, I would go look at fanfic. You know, fanfiction, these people who write Harry Potter alternative universes and all this kind of stuff. It's from the bottom-up. That's very alternative. That's alt-something. And so whatever it is you're involved in, I think it's really important that you go broader serendipitously. Try something. Alvin Toffler, who was a futurist, had a great gimmick, 'cause he would go around the world giving these talks at conferences, and he said every time, he would always go walk around the hotel to the other conference that was happening at the hotel and just attend. It didn't matter what it was. It could have been the hairdressers of America. It could have been the realtors. Whatever it was, he would attend that other conference after he gave his talk and before, and he said, it was never always paid off. And just having him think about something or encounter something that wasn't on his horizon, that he understood, well, this is connected. What is a form of powerful medicine? Oh, boy. Reading. Favorite books? A couple, two or three? Favorite books. Yeah, or books to recommend. How about not favorite. Let's do this. Let's do recommended. Because favorite and recommended are often very different. Yeah, so I'm reading a book right now that's very interesting called Superforecasters. Generally, predicting thing, always wrong. People like me are always usually wrong. But it turns out that with training, you can actually become better at predicting. And so, this guy... Is it pattern recognition, the core of it, or what is it? No, it's not that, because it's actually unlearning. It's actually being able to forget certain things and to question the assumptions. And finding patterns, we kind of overfit things. We tend to find patterns that we have preconceived notions of. 'Cause it's based on the boundaries of your knowledge, yeah. Right. It's letting go of those preconceived things that's really the heart of it. Powerful medicine. Right. Got it. Any other books you'd recommend? Oh, my gosh. I read a lot of science fiction when I was a teenager. It was very influential. Like Dune. Dune, yeah, Stranger in a Strange Land, Foundation Series, Asimov, the classical, golden era. I didn't read very much in my 20s and 30s, partly 'cause I was traveling, and partly 'cause I just lost interest and maybe the Hollywood movies took over. But recently, I've been reading more science fiction and going back to it, because there's a whole 'nother generation, it seems, of really good stuff. And I read Ready Player One, which was fun, amazing, cool. It's about VR world. Some recent Neal Stephenson. The Three-Body Problem, which is from a Chinese author. It's the first Chinese science fiction that's come back into English. It won the Hugo Award this year. An amazing book, really far-out, but also, it's very Chinese at the same time. It's kind of hard to explain. An individual outside of your line of work that we should know about. A human. Oh, boy. He's not outside my work, but I am such a fan of Stewart Brand. If you don't know Stewart Brand, you should go read what he's been writing, what he's thinking about. He's a cultural innovator for 50 years, and almost every, at the core of almost every thing in the last 50 years in America. He's been almost at the edges or the center of it, has had a role in it, and he'll teach you, if you pay attention, about how to think different. And that's what I got from him, how to think different. Be a good name for an ad slogan, wouldn't it? (both laugh) Kevin, thank you so much for your time. It was my pleasure. It was great. I could talk to you for the next 10 years, and so could the, I'm sure the folks could listen forever. Best place to find you on the internet? I have a very simple email. Kk@kk.org, which has been public for 30 years, and I have a website. It's the same thing. Kk.org. Sweet. Thank you so much, good sir. Great. Signing off, another episode. Stick around, and we'll help you sign up at creativelive.com/30daysof, 30, the number 3-0, daysofgenius. This was Kevin Kelly, and there's lots of other folks there. (steady electronic music)

Ratings and Reviews

Rory

I have watched all 30 days so far and the first thing that blows me away is how Chase interviews all these different people, totally relaxed and he listens to everything they say and finds a question that relates so clearly to the subject being talked about. He also brings in quotes and snippets for other people, how he remembers all this stuff is just amazing. This is what I have taken away from the first 5 interviews. Mark Cuban started the series theme with the concept: you can start from nothing and become something by way of the HUSTLE. Although it sounded like whatever he touched turned to gold immediately, there was a huge amount of hustle that went with it to get it all going. Seth Godin was down to earth and lead with "happiness is a point of view", so do something today that will make tomorrow worthwhile being there. Be prepared to fail to succeed. Marie Forleo the Jersey girl made good. Her dad told her to do what you love. So she set out to do just that. It didn't happen over night, loads of job frogs kissed, until the life coaching vibrated through her life with the help of intuition and she was set on her path to success. Navigate passed those that will drag you back or down was another insight from Forleo. Using the concept from her Mom, ‘everything is figureoutable’, stood her in good stead all her life. Having a close community to help you is essential. Stop whining and just do it. Read Cameron Herold's double double, lean into your future. Tim Ferriss, the whirlwind learning man, using the simplistic steps to learn anything is the Ferriss way to go. you want to be a Tango champion, go to Argentina and learn from the best. Hard work has its place but control it. Another Ferriss phrase is 'what would this look like if it were simple', following this concept takes the complexity out of what you are doing and leads to you accomplishing the task you are undertaking. Celebrate the small wins and you accomplish the large ones. Meditation makes one more effective. Play at creativity to keep creative. Don't retreat into the story of the voices. Arianna Huffington, what Greece as a country could do with to get itself out of the slump. Remember you are not your job, don’t stifle your creativity. You don’t have to burn yourself out to succeed in life. The obnoxious roommate the keeps you awake and hurts your creativity. Sleep is not only life affirming but also imperative for the brain to reboot and spam filter.

Mich

I just paused this course to take a breather, overwhelmed with how people are willing to share advise, stories and insight....such powerful ones to help each other!!! I think the world is an amazing place and these times are the best that we could be in...yes sometimes life is tough but we have so many great people and so many people doing such great work....i love and admire Chase Jarvis and what he has done with creative life!!! Thankyou Chase, this is just wowwww!!!!

Julian Hartwell

I stumbled across these interviews on YouTube after delving into some similar content in my 'motivation hour' circa breakfast when I need some good energy for the day to get me in the right head space. And boy am I happy I did!!! Every single one of these is awesome, unique, insightful, and helpful in sooo many ways to my path as a creator, maker, entrepreneur, etc. Not only does each guest Chase have on this series drop a ton of gems in general...they all provide a wholly unique perspective and temperament, as well as life story for how they got where they are today! While many of their insights are similar after a fashion, for how they reached 'success'..they also really help illustrate how success is differently measured by each individual, and that no two paths are ever the same. I respect Chase for just his selection alone, because he seemed to get the whole spectrum of human temperaments/types in these interviews, and they come from so many different fields. And while these people have alot to say, it's also HOW Chase poses his questions and steers the conversation that make them so enjoyable to listen to. It's almost easy to take for granted how good an interviewer he is until you realize whoa...they just covered ALOT in not even that much time! Needless to say I'm a fan..and I haven't even watched em all yet! (pacing myself) Five Stars here! Go Watch and get Inspired!!! -Julian H Pianist, Composer, Bandleader www.julianhartwellmusic.com

Student Work

Related Classes

Creative Inspiration